By Emmanuel, Mikal & Marion

The cabaret was a place that brought together different social classes, which do not usually mix. It was also a place of refuge, a safe place for people who were excluded from society. The cabaret allowed different people, who went through trauma or who were discriminated against by society, to have a place of refuge but also a place which allowed them to find recognition and make a breakthrough as well as giving them the opportunity to create links with other people who came to the cabaret.

Indeed, cabaret offered a voice to marginalized artists and performers, who did not find a place in traditional artistic circuits and who were able to express themselves more freely in an alternative framework. This has also helped to diversify the art scene.

Artists have used cabaret to address social and political issues, which created a sense of solidarity and belonging.

Some cabarets have helped deconstruct stereotypes by offering representations of sexuality, gender identity and other aspects of day-to-day life. These spaces played an educational role by exposing the public to diverse perspectives and promoting the understanding of others.

It was during the Belle Époque that the cabaret experienced its biggest growth. The expression “Belle Époque”, which spread throughout the twentieth century, reflects a somewhat distorted and embellished perception which is nevertheless based on a certain number of realities: the political stability, the rapid economic growth oriented towards modernity, the improvement of the quality of life of French citizens, which was accompanied by a reduction of poverty and the development of leisure and sporting activities.

During this period, French society was very hierarchical, but people began to realize that they belonged to a single nation and, therefore, that different social classes could coexist.

Artists began to deviate from realism to give birth to abstract art, art nouveau which was an avant-garde style. Social dance practices at balls or in cabarets brought people together, regardless of their social class.

One of the great cabaret personalities of this period was Jane Avril, who defended personal development and healing psychological trauma through dancing. She was one of the most famous dancers of the Moulin Rouge, she was also the ambassador of the French cancan to European capitals. She was revolutionary in the modern dance scene.

We think that through her personal story, it is easier to understand the importance of cabaret, its history, and the different ideas it defends. This will help us understand the importance of cabaret as a place of refuge and expression for people who are discriminated against. So: what is the legacy of Jane Avril?

Jane Avril’s childhood and her beginning

Jane Avril, whose real name was Jeanne Louise Beaudon, was born on June 9, 1868 and died on January 17, 1943. Jane was raised by her abusive mother. At the age of 13, she was committed to a psychiatric hospital called the Salpêtrière, for “ovarian hysteria”. At that time, the internment of women could easily be carried out at the request of fathers, husbands or even brothers for generally futile reasons such as refusal of marital duty, a refusal to do housework or even for reading novels.

In the case of Jane Avril, we understand through the various studies that have been carried out that she suffered from epilepsy.

It was therefore during her internment at the Salpêtrière that she discovered her passion for dance, more precisely during the Bal des Folles, which was an event where everyone in Paris was invited to a big ball in the company of the various hospitalized women. It was a sort of “human zoo”, in fact those women were exhibited for public therapy or hypnosis sessions. This event was an attraction for outsiders, it was also eagerly awaited for by women who were interned since it allowed them to briefly break away from the routine of their confinement.

It is during one of those events that Jane had a seizure, she started dancing like a “crazy woman”.

She saw dance as a soothing remedy. In fact, she grappled with the psychological challenges resulting from the mistreatment she endured through the medium of dance.

Her success in the world of cabaret

Weakened by her trauma, illness, and various hospital stays, Jane attempted to end her life by throwing herself into the Seine. After her suicide attempt, she was taken in by the keeper of a Parisian brothel. She discovered the Parisian nightlife, where women were half dancers and half prostitutes. It was at the Bal Bullier that her career as a dancer began. She discovered she had a gift for dance, and was noticed for her style, her seductive movements and her outstanding personality.

In 1889, she met Charles Zilder, the founder of the Moulin Rouge. He decided to hire her in his cabaret. From the very beginning of her career, Jane set herself apart through her distinctive style by performing solo, and by crafting her own choreographies and costumes. She wore exclusively red underwear, whereas at the time dancers wore white underwear.

She went on to become an emblematic figure of the French cancan. This new style of dance was introduced to cabarets by Joseph Oller. The ambition of the co-founder of Le Moulin Rouge was to create an entertainment venue with a new way of dancing in which the dancers lift their legs to reveal their underwear. Jane once again stood out for her style, with no vulgarity and more modesty. This was a point that she asserted herself, insisting that she was not a prostitute but a dancer.

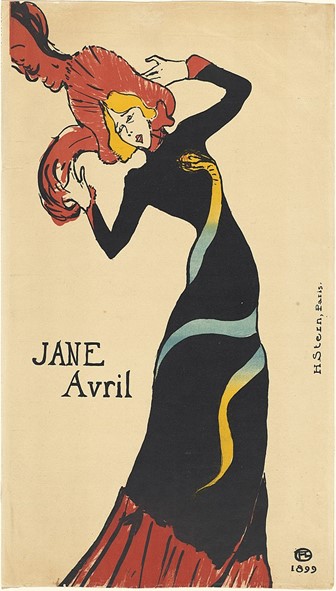

She was also an emblematic figure in the works of Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, a Montmartre artist who befriended Jane. He produced a large series of posters of Jane dancing.

Mainly known for her roles at the Moulin Rouge, she also made her mark on other Parisian stages such as the Décadents, the Divan Japonais, and the Folies Bergère. She was known as Melinite, the name of an explosive, referring to her exaltation for dancing. She represented the embodiment of dance. On stage, she transmitted great energy and grace and was seen as an acrobatic dancer.

Jane Avril, a Lasting Influence

Artistic Legacy

Jane Avril has left a lasting artistic legacy, thanks in large part to the pictorial representations by artist Toulouse-Lautrec, who took her as one of his muses.

Toulouse-Lautrec’s iconic works highlight Jane Avril’s magnetic presence on stage and her contribution to the art of the French cancan. Her unique style and charisma are vividly captured in these paintings, making her an icon of the era. A notable aspect of Jane Avril’s legacy is her role in the evolution of the French cancan. With her energy and presence on stage, she left a lasting impression with her solos. Her innovative approach opened new possibilities for dancers to express themselves individually and showcase their unique talents. In fact, it is thanks to her that we have the tradition of solo dancers wearing red stockings. Originally a demand on her part, it has now become a customary attire for all solo dancers in the French cancan.

Artistic Innovation

The collaboration between Jane Avril and Toulouse-Lautrec also contributed to the emergence of Art Nouveau, an artistic movement characterized by its inventiveness, organic motifs inspired by nature, and bold use of colors. The striking images of Jane Avril dancing, immortalized by Toulouse-Lautrec, served as inspiration for many Art Nouveau artists to create posters and illustrations that captured the energy and vitality of dance. Toulouse-Lautrec’s poster depicting Jane Avril dancing with an expression of joy and vivacity has become one of the most iconic images of Art Nouveau. This poster, with its fluid lines, vibrant colors, and floral motifs, perfectly embodies the aesthetics of this artistic movement.

Contemporary Influence

Jane Avril has directly and indirectly influenced contemporary dance as an inspiring model. The fundamental values of contemporary dance include the liberation of the body, creativity, and expressiveness, all of which Jane Avril embodied in her own dance. For example, contemporary choreographer Marie Chouinard drew inspiration from Jane Avril to create choreographies that explore freedom of movement and bodily expression. In her performances, Chouinard uses expressive gestures and postures, while playing with the stage space in a similar way to Jane Avril. Similarly, Belgian choreographer Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui draws inspiration from Jane Avril’s innovative approach to create pieces that blend tradition and modernity, integrating elements of historical dance into a contemporary context.

Social legacy

19th-century society forbade women the slightest desire of ambition and freedom, and Jane Avril’s journey goes against this assertion. She broke the rules and had an impact on changing the vision of the role of women in society especially in cabaret. She made it clear she was not a prostitute but just a dancer. At a time when women conformed to what society expected of them, Jane was provocative and created a new representation of women. She refused to conform to the expectations and the traditional conventions of the cabaret dance. By dancing alone she showed that a woman can be autonomous, expressive, and creative, inspiring many women to break away from the roles they had been assigned for years.

The complicated childhood of Jane Avril led her to discover dance and cabaret. A place in which social norms are often set aside. It also allowed her to find a place to assert herself and confront her mental health. During her career, she set herself apart from the rest for her style and made an impact on the artistic and social aspects, leaving behind a strong and lasting legacy that remains a benchmark still to this day.